When I finished reading Mamadou Kwidjim Toure’s piece on the paradox of gold-rich nations like Burkina Faso borrowing in dollars, I had to pause.

Not because the idea was new—but because of how precisely and patiently he laid bare a truth we’ve long known but often shy away from naming: money is not neutral. It’s a political weapon. And trust, in financial systems, is as manufactured as any product of colonial legacy.

Toure opens by asking a deceptively simple question: Why do we trust printed pieces of paper more than grams of gold dug up in Burkina? And as someone who’s worked in both development finance and international policy, I can tell you this question cuts to the core of decades of imposed economic orthodoxy.

I’ve been in rooms in Washington D.C., Brussels, and Addis Ababa where entire nations’ budgets were debated in currencies they didn’t control. Where policy advisors talked about “reserves adequacy” without once questioning why African reserves had to be denominated in dollars or euros in the first place. Toure, with quiet insistence, reminds us: the architecture of global finance was designed at a very specific moment—Bretton Woods, 1944—to reflect the geopolitical and economic might of the United States, not the collective interests of sovereign nations.

The dollar became the reserve currency not merely due to U.S. gold reserves or industrial output after WWII, as Mamadou rightly outlines, but also through a sophisticated entrenchment of institutional infrastructure: the IMF, the World Bank, SWIFT, and the entire Eurodollar market that developed in the 1960s. These were not accidental outcomes—they were strategic constructs.

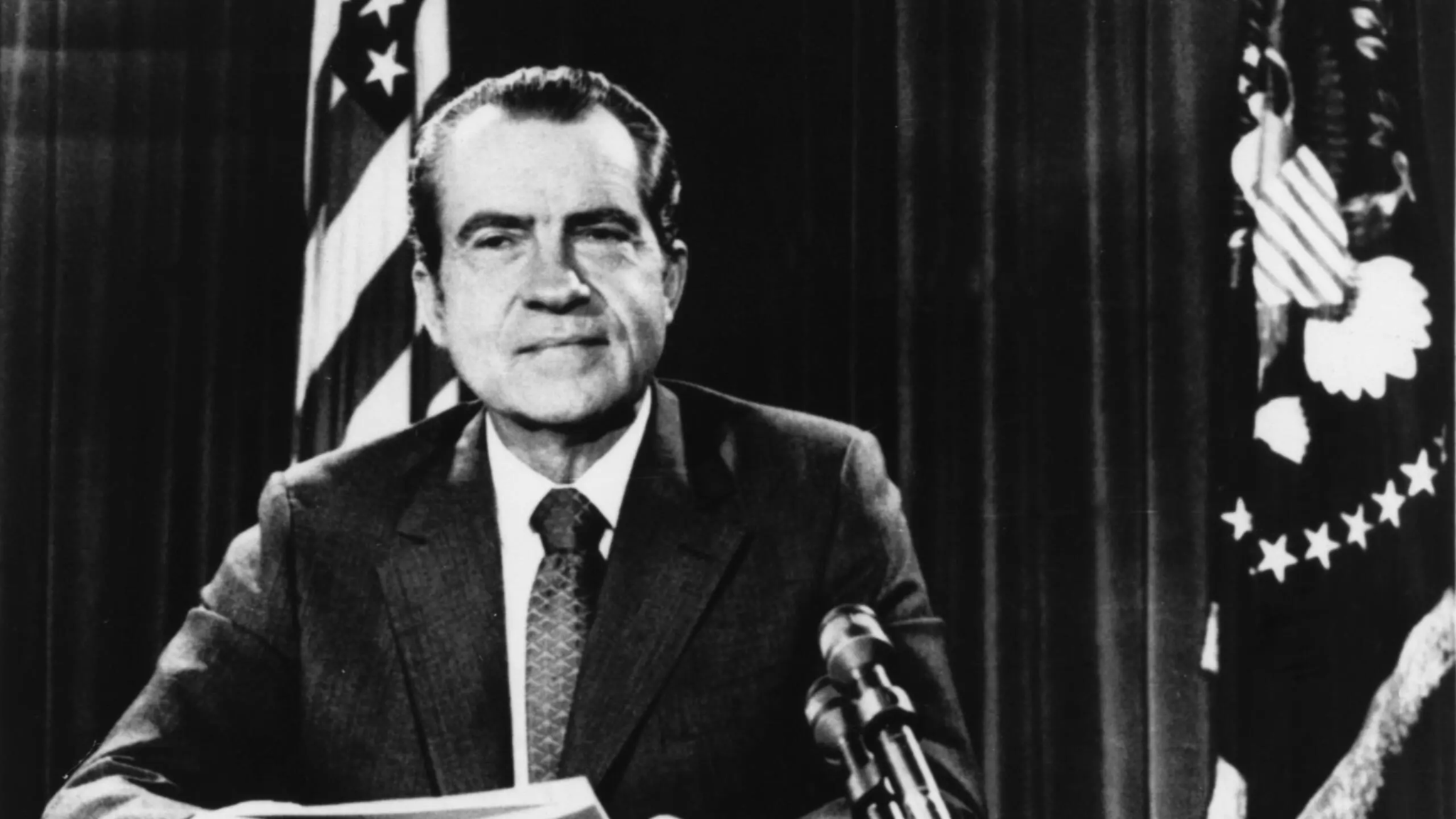

And then came Nixon’s 1971 decoupling from gold, a decision that Toure frames not as an event, but as a redefinition of money itself. I found this part of his narrative particularly powerful. Because most people still treat fiat money as a natural evolution, when in fact, it was a strategic rupture. It allowed for unprecedented financialization, speculation, and credit expansion—none of which benefited the average Burkinabé miner whose gold was still being traded in the now “unbacked” dollar.

This part of the story hits home for me. I once worked on a sovereign debt restructuring proposal for a West African country. The largest line item in their liabilities? Dollar-denominated loans for infrastructure built by Chinese firms. But what caught my eye was the collateral: gold export revenues pledged to repay those loans, routed through offshore accounts. This is the system Toure describes—not broken, but extractive by design.

He goes on to explain how Burkina Faso, despite producing over 60,000 kilograms of gold annually (the fifth-largest in Africa), sees most of this wealth exported with little retained value. The national efforts to nationalize mines, build a local refinery, and force mining companies to bank locally are not just policy moves—they are acts of monetary defiance.

And of course, these moves are punished. I’ve seen firsthand how “risk premiums” suddenly rise in international lending when African nations attempt economic autonomy. How headlines shift tone. How Moody’s and Fitch begin whispering about “political instability.” Toure’s observation— “challenging the established order comes with consequences”—couldn’t be more accurate.

What I appreciate most is how Toure doesn’t leave it there. This essay isn’t a lament. It’s a blueprint. He connects this structural critique to an emergent opportunity: the tokenization of gold. Digital currencies backed by real assets. Local miners issuing tokenized representations of their yield. Communities bypassing intermediaries.

This vision is already being tested. Zimbabwe, after facing currency collapse, introduced a gold-backed digital token in 2023, known as the ZiG. And Ghana, where I’m currently based, is exploring a similar model under its “Ghana Gold for Oil” barter scheme. These aren’t perfect solutions. But they represent a deeper shift: the idea that value must come from the community, not just through foreign validation.

And when Toure says, “systems persist until they don’t,” I think of Argentina’s dollar peg in the 1990s. Of Lebanon’s pound collapse. Of Venezuela’s bolívar. No currency system is permanent—not even the dollar’s dominance. Especially not when over 40 countries now trade in currencies other than the greenback.

His essay ends with a moral provocation: Why should people trust abstract promises over physical reality?

In a world of inflationary fiat, manipulated credit cycles, and geopolitical coercion, it’s a question we can no longer afford to ignore. If Africa is to chart a new monetary path, it will be because of voices like Mamadou’s, willing to expose the design—and redesign it.

You should read his full article. It will change how you think about money, value, and power.

About Author: –

Mamadou Kwidjim Toure, a Global Finance Expert and Philanthropist Pen down his thoughts on Burkina. Foreign powers are trying to destabilize what they call the “second poorest country in the world”, but maybe it’s not as poor as we believe. For more such articles follow mamadou